Did you know that the science of producing safe raw milk was flourishing way back in the late 1800’s? Read on for an interview with Dr Edward Tindall DVM, who worked at the Walker-Gordon Certified Raw Milk dairy in New Jersey.

Aerial view of Walker Gordon Laboratories and Dairy in Plainsboro, New Jersey.

Certified Medical Milk

Humans have had a long and successful history with raw milk for at least 10,000 years. Ancient peoples who consumed milk had a competitive advantage over those that did not have a steady source of readily available food, such that the reproductive capacity and/or survivability of ancient raw milk drinkers was substantially increased compared to non-milk-drinking populations.

After numerous millennia flourishing with raw milk, mankind’s relationship with raw milk took a wrong turn. By the mid-1800’s in America, some raw milk production had shifted away from farms and into highly-populated cities. Big cities did not have pastures or clean water, and the cows in city dairies were kept in filthy conditions with poor nutrition and poor animal health. Many of these cows were fed byproducts from alcohol distilleries, leading to illness in the cows. Raw milk had become a source of deadly diseases such as tuberculosis, typhoid, diphtheria, and scarlet fever.

In the late 1800's, it was recognized that raw milk being produced in these conditions was dangerous, and two solutions were proposed. Pasteurization was ushered in to address filthy conditions and unhealthy cows in cities. It answered the question of how to commercialize dirty milk, rather than spending the time and energy it would take to produce clean milk from healthy cows. The other solution was to actually produce the milk in hygienic conditions with healthy animals.

It was known that raw milk was a superior source of nutrition for infants and children, so the American Association of Medical Milk Commissions (AAMMC) was established in the late 1800's by Dr Henry Coit to ensure a supply of safe raw milk. The AAMMC was in operation for nearly a century, certifying medical raw milk for use in hospitals and for feeding infants and children.

“The requirements of the New York Commission at that time were: ‘That the milk should contain 4 to 4.5 percent fat; that it should be free from pathogenic germs; and that the total number of bacteria should not be excessive. The milk was to be delivered in bottles and not over 24 hours old. It should be from healthy cows.”

~Walker-Gordon: One of a Kind

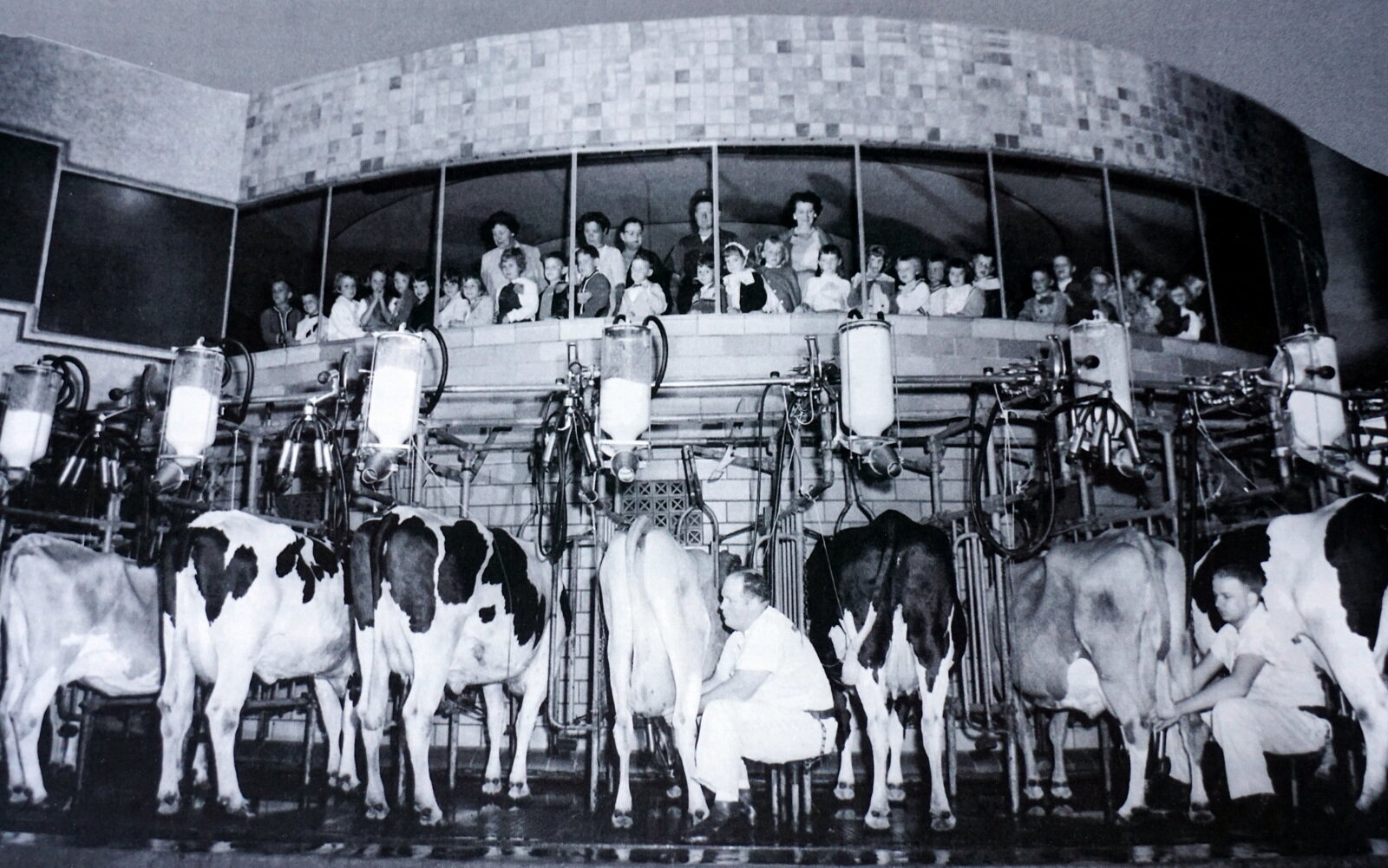

Walker Gordon’s Rotolactor in operation. School buses, tour buses, and families accounted for approximately 250,000 visitors annually.

Walker-Gordon Dairy and Dr Edward Tindall DVM

The Walker-Gordon dairy farm was a preeminent source of Certified Raw Milk for over 70 years. Edward Tindall’s father worked at the Walker-Gordon farm, and he himself worked at the farm for several summers. Edward went on to become a practicing veterinarian in New Jersey for nearly 40 years, and also developed implantable microchip technology for animals. The Raw Milk Institute is pleased to have Edward Tindall DVM on our Advisory Board.

In the late 1990’s, Edward co-authored a book about the Walker-Gordon farm titled Walker-Gordon: One of a Kind. Edward was kind enough to share more information about this extraordinary farm in a written interview.

1. Can you tell us about what made Walker-Gordon dairy farm so special?

Walker-Gordon was never intended to be just a dairy. The actual name was Walker-Gordon Laboratory Company, imprinted on their bottles and responsible for numerous innovations in the field of dairy. Among these were the first rotary centralized milking parlor, milking 1650 head. 50 cows were milked at a time (every 12 and a half minutes or one revolution) on the ʻRotolactorʼ.

The milk was immediately refrigerated, and if intended for the Philadelphia, New York or Boston market, shipped within hours from a refrigerated box car of the Pennsylvania Railroad on a siding adjacent to the milking parlor.

The cows were attended 24 hours a day by herdsmen in 50 cow barns with constant attention to keeping the cows bedded on fresh peanut shell bedding and groomed, with ever present fresh water on demand, fed grain and excellent alfalfa hay year-round.

Other innovations were the addition of irradiated yeast to feeding regimens to enhance vitamin D (prophylaxis against childhood rickets), production of acidophilous milk for enteric health, harvesting crops at prime time for storage regardless of weather conditions, use of byproducts (fecal waste) for garden fertilizers, artificial insemination, crop production by cooperative farms under control and supervision of central organization, and extensive record keeping of health and productivity of each cow.

Bottling was done immediately adjacent to the Rotolactor. The milk, "certified and unpasteurized," was not exposed to anything but sterilized stainless steel and glass.

2. What production and milking practices were used to keep the milk safe for people?

Cleanliness was ever a constant protocol. The cows were pre-washed with warm water prior to entering the milking parlor. There they were toweled by attendants in white uniforms, attached to sterilized stainless steel milkers, and the milk fed to Pyrex glass containers and delivered through stainless steel pipes to the bottling plant adjacent to the milking platform.

All milking personnel had weekly examinations and throat cultures by the local physician. Milk was routinely cultured in an on-site laboratory for bacterial counts and pathogens.

3. Since you were employed there for a time, tell us about what you did and what it was like to work there?

My employment was several summers working on maintenance and the storage of alfalfa hay. During haying season the crop was harvested at prime time regardless of the weather. Chopped in the field, blown into stake bodied trucks and delivered to the massive dehydrators, it was compressed into 110 to 130 pound bales around the clock. Starting a 7:00 am, the hay was stored in large barns, often in 120 degree summer temperatures.

Hay being delivered to the dehydrator for preservation. In later years, it was chopped into more manageable size for compression and baling.

4. What kind of milk did this dairy produce?

Walker-Gordon produced Grade A, whole milk, unpasteurized of the highest quality the industry has ever known, from its inception in the earliest years of the twentieth century until it stopped production in 1971.

“For those of us who grew up with the taste of fresh, really fresh, whole milk, unadulterated in any manner except to chill it ice cold, today’s milk is a sad replacement…

The unequaled taste of an ice cold half pint of milk, the cream layered on the top, after working several uninterrupted hours in excessively hot temperatures… I have yet to equal that flavor…”

~Walker-Gordon: One of a Kind

5. Who were the usual customers for this milk?

The customers were the general public locally, with home delivery, and public markets from Washington, DC to Boston, Ma. A renowned quality product hailed for freshness and longevity, it had a very loyal consumer base. President Franklin Delano Roosevelt, when traveling abroad by ship, insisted that Walker-Gordon milk and cream be available, on board, for the trip.

6. What was the safety record of this dairy that operated for about 8 decades up until 1971?

The safety record of Walker-Gordon milk and milk products was above reproach and I can find no instances (nor have I heard of any) of any untoward or adverse instances of health problems or lawsuits. Safety of personnel was extremely good. Farm accidents are ever present and WG had some, but fewer than would be expected.

“Cheaper milk from the heartland of America, increased labor costs, higher taxes, wages, and insurances, difficulty in attracting farm labor, the sky-rocketing value of land, and pressure for housing for an increasing and increasingly affluent population all contributed to the demise of farming in general, in New Jersey and elsewhere, and in particular to Walker-Gordon with its emphasis on high quality, first and foremost.”

~Walker-Gordon: One of a Kind

7. What future potential do you see for raw milk dairy farming?

Prognostications of the future of raw milk dairy farming is fraught with the same magnitude of variables as the future of the country. I would like to believe that the future is positive, for indeed, I can think of no more beneficial product than clean, wholesome, properly handled raw milk that is fresh from the cow and unaltered by pasteurization or other untoward handling.

The vicissitudes of government and the legal profession, swayed by propaganda and functioning under ignorance of biology and a mindset that excludes information that does not align with biased public opinion is a very large hurdle to clear. As long as there is a discerning public with the economic wherewithal to acquire a quality product, the market is assured. I admire the efforts of individuals such as Dr. Joseph Heckman and Mark McAfee that take up the torch, live and advocate the premise, and forward such a noble cause.

Paving the Way with Safe Raw Milk

The Walker-Gordon dairy was certainly an exceptional dairy. Walker Gordon’s eight decades of safe raw milk production are an imminent example of what can be achieved through dedication and innovation. At its peak, the Walker-Gordon dairy was producing 6,500 gallons of milk daily. Through hygienic practices and regular bacteria testing of its milk, Walker Gordon dairy was able to provide safe raw milk for thousands of people over several generations.

The last Certified Medical Milk dairy in the USA was Alta Dena dairy in Los Angeles, California. Alta Dena produced its last quart of raw milk in May of 1999. With the end of the American Association of Medical Milk Commissions and their certification of raw milk dairies, there was a great need for leadership in safe raw milk.

The Raw Milk Institute (RAWMI) was created to fulfill this need. RAWMI teaches well-established scientific principles and good production methods to assist farmers in producing hygienic, safe raw milk. Through its LISTING program, RAWMI assists farmers in developing risk analysis and management plans (RAMP) for their unique farms. RAWMI’s Common Standards have set an international benchmark for bacterial testing of raw milk.

Edward Tindall’s book, “Walker-Gordon: One of a Kind” is available from Covered Bridge Press, 39 Upper Creek Road, Stockton, New Jersey 08559 at $25 dollars per copy, plus USPS shipping. Covered Bridge Press can be reached at 908-996-4420.

Walker-Gordon: One of a Kind. Book by Edward Tindall, DVM.